WHAT IS WRIST FRACTURE?

Figure 1 showing the two forearm bones - Radius and Ulna

The wrist is made up of eight small bones and the two forearm bones, the radius and ulna (see Figure 1). The unique shape of the bones gives the wrist a freedom of motion; allowing it to bend and straighten, move side-to-side, and rotate palm-up and palm-down.

A fracture may occur in any of these bones when enough force is applied, such as when falling down onto an outstretched hand. Severe injuries may occur from a more forceful injury, such as a car accident or a fall off a roof or ladder. Osteoporosis, a common condition in which the bone becomes more brittle, may make one more susceptible to getting a wrist fracture.

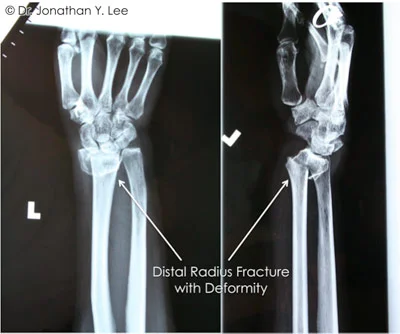

Figure 2 showing the distal radius fracture with deformity

The most commonly broken bone of the wrist is the radius (see Figure 1). When the wrist is broken, there is pain, swelling, and decreased use of the hand and wrist. The wrist often appears crooked and deformed (Figure 2).

Fractures of the small wrist bones, such as the scaphoid, are unlikely to appear deformed (see Figure 1). Fractures may be simple with the bone pieces aligned and stable. Other fractures are unstable and the bone fragments tend to displace or shift, in which case the wrist is more likely to appear crooked. Some fractures break the normally smooth, cartilage-lined joint surface; others will be near the joint but leave the joint surface intact. Sometimes the bone is shattered into many pieces, which usually makes it unstable. An open (compound) fracture occurs when a bone fragment breaks through the skin, and this increases the risk of infection.

HOW DO I KNOW IF I HAVE WRIST FRACTURE?

Figure 3 showing distal radius fracture with deformity

Examination and x-rays (Figure 3) are needed so that your doctor can tell if there is a fracture and to help determine the treatment. Sometimes a CT scan or MRI may be used to get better detail of the fracture fragments and associated injuries. In addition to the bone, ligaments (the structures that hold the bones together), tendons, muscles, and nerves may also be injured when the wrist is broken and these injuries will need to be treated in addition to the fracture.

HOW ARE WRIST FRACTURES TREATED?

Figure 4 Distal Radius Fracture treated by cast immobilisation

The pattern of the fracture, whether it is displaced or non-displaced, whether the joint surface is involved, and whether it is stable or unstable are all factors in determining the method of treatment. Other important considerations include your age, overall health, hand dominance, work and leisure activities, the presence of any prior injury or arthritis, and if there are any other associated injuries. A splint or cast may be used to treat a fracture that is not displaced, or to protect a fracture that has been set in position (see Figure 4).

Figure 5 Surgery to stabilise the fracture with internal and external fixation

Surgery may be required to treat certain other fracture types in order to properly set the bone and/or to stabilise it. Fractures may be stabilised with external fixation or internal fixation. External fixation utilises an external frame comprising an external rod and pins places into the bone above and below the fracture site (Figure 5), keeping the bones in position until healing occurs in 4 to 8 weeks.

Internal fixation uses plates and screws (Figure 6) placed directly against the bone around the fracture site to stabilise the position of the fracture fragments. Modern implant technology has improved significantly and can allow more accurate restoration of bone and joint anatomy, a more rapid return to function and commencement of physical therapy, while also avoiding the use of cumbersome plaster casts and external frames.

Figure 6 Internal fixation of distal radius fracture with plates and screws can avoid prolonged immobilisation in a cast, and allow early movement and physical therapy

Sometimes arthroscopy is also used in the evaluation and treatment of wrist fractures, especially if the joint surface is involved in the fracture. Your hand surgeon will determine which treatment is the most appropriate in your individual case.

On occasion, bone may be missing or may be so severely crushed that there is a gap in the bone once it has been re-aligned. In such cases, a bone graft may be necessary. In this procedure, bone is taken from another part of the body to help fill in the defect. Bone from a bone bank or synthetic bone graft substitutes may also be used.

While the wrist fracture is healing, it is very important to keep the fingers flexible, provided that there are no other injuries that would require that the fingers be immobilised. Otherwise, the fingers will become stiff, hindering the recovery of hand function. Once the wrist has enough stability, motion exercises may be started for the wrist itself. Your hand surgeon will determine the appropriate timing to commence these exercises, and plan a course of hand therapy for rehabilitation and restoration of flexibility, strength, and function.

Recovery time varies considerably, depending on the severity of the injury, associated injuries, and other factors as noted previously. It is not unusual for maximal recovery from a wrist fracture to take several months. Some patients may have residual stiffness or aching. If the joint surface was badly injured, arthritis may develop. On occasion, additional treatment or reconstructive surgery may be required.